In Part One of this blog series we took a historical look at some of the many guises of the Little Malop Street Mall, an area of public space in the heart of Geelong. In this, Part Two of our story about Geelong’s Little Malop Street Mall, we will explore in more detail what this story reveals about the status of public space in the 21st century, and the dynamics of social and economic inequality in the post-industrial city of Geelong.

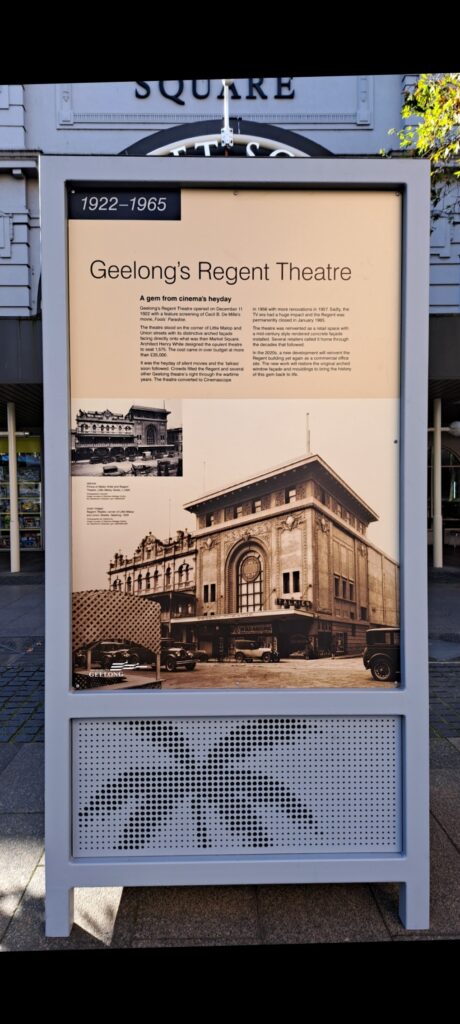

At the start of the third decade of the 21st century, the two sides of Little Malop Street are a study in contrasts. Little Malop is dissected into its ‘Western’ and ‘Eastern’ ends by the major thoroughfare of Moorabool street. The trendy Western end of Little Malop Street is regarded as a success story of efforts to revitalise Geelong’s CBD. It is home to boutique bars, cafes and restaurants that form a thriving night-time economy. It goes some way towards restoring the ‘laneway’ culture that existed in McCann and Jacobs Streets but that Geelong City Council and other stakeholders realise in hindsight was effectively destroyed with the construction of Market Square shopping centre. Across Moorabool Street, in the beleaguered mall, it is similarly property developers and business interests who are seeking to spearhead ‘revitalisation’ efforts. Witness the Hamilton Property Group’s redevelopment of the former Regent Theatre, under construction at the time of writing. A noticeboard erected in the mall announces the project to the public (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: A noticeboard advertises the Regent Theatre redevelopment taking place in the vicinity of the Little Malop Street mall, as photographed in August 2023. Image author’s own

The project boasts that it will restore many of the original features of the façade, which in the late 20th century had been rendered in a brutalist block concrete style (see Figure 2). The building was used most recently as a discount store before sitting idle for many years. As the noticeboard reads, ‘the new work will restore the original arched window façade and mouldings to bring the history of this gem back to life’.

Figure 2: The building at the corner of Little Malop and Union Streets, formerly the site of the Regent Theatre, is being redeveloped in 2023 by the Hamilton Property Group. Image author’s own

The Hamilton Property Group’s stock in trade is to take key pieces of Geelong’s industrial-era architecture and transform them into high-end commercial office space. The Group also lists the redevelopment of the Federal Mills buildings in North Geelong in its portfolio. The site of one of the city’s many textile factories, the Federal Mills were reimagined by the Hamilton Group as a co-working space and hub for start-up businesses. This project was lauded by commentators as helping to inject a sense of renewal and optimism into perceptions of Geelong’s future, in the aftermath of the closure of the city’s remaining large manufacturing industries, the Ford Motor Company and Alcoa aluminium smelter (see for example, the ‘Hubcaps to Creative Hubs’ documentary series). This is a recipe for revitalisation through gentrification. These ideas are not new, nor are they unique to Geelong. In pushing rents even higher, gentrification does little to address the problem of empty shop fronts in the city centre – in fact, it only exacerbates it.

The work of urban studies theorist Richard Florida, in particular his theorising of the ‘creative class’ and its role in processes of urban development has, since the early 2000s, been a particularly compelling influence in Geelong and other industrial centres seeking a ‘fix’ to the problems of faltering and uneven economic growth. Florida (2014) suggests that the activities of a ‘Super-Creative Core’ of professionals, a diverse group that includes scientists and engineers, university professors, artists, designers, as well as ‘thought leaders’, writers and researchers, among others, are increasingly central to processes of innovation and economic development. The challenge for jurisdictions seeking to attract the creative class to their shores is to understand what makes the members of this class tick – Florida suggests that a culture of open-minded bohemianism and tolerance is particularly generative for the creative class.

In Geelong, as elsewhere, Florida’s ideas have been interpreted by economic development authorities as reinforcing the need for ‘place branding’ efforts, and justifying private property developers having an even greater role in processes of urban development. In 2016, the Committee for Geelong, one of several groups which pursue the strategic economic and business interests of the region, commissioned an international study tour to examine what makes so-called ‘Second Cities’ – such as Cleveland and Pittsburgh in the US, and Sheffield and Liverpool in the UK – successful. In its final report, the Committee notes that in such places as Dundee, Cleveland and Pittsburgh, ‘there is…a recurring emphasis on creating vibrant city centres as an attractor of new residents and businesses, particularly millennials’. Florida’s ‘creative class’ theory has a central place in the recommendations they propose for the ‘Branding of Geelong’:

The lifestyle and amenity attributes of Geelong can be used to attract new residents to the city…the continued development of [the] city centre as a place for shopping, culture, entertainment and dining can build on this appeal, particularly for what Florida (2004) refers to as “the creative class”. The marketing and improvement of Geelong as a place to live is an ongoing priority. (Correia & Denham 2016, p.81)

Many years after they first touched down in Geelong, Florida’s ideas continue to resonate among local business and civic leaders. In 2017, the vision of Geelong as a ‘Clever and Creative City’ was launched as a 30-year strategy guiding the region’s economic development into the future (City of Greater Geelong 2022). However, at the same time as the city centre was conceptualised as increasingly central to urban renewal efforts, it faced one of the biggest threats to its viability. As manufacturing took a downturn in many of Australia’s industrial towns and cities in the late 20th century, small businesses were collateral damage in the flight of industrial capital. The ‘Renew’ concept that originated in 2008 in Newcastle, NSW, promised a ‘solution’ to the problems of urban blight that many Australian towns and cities were grappling with. The Renew model was to reactivate vacant commercial spaces through the brokering of short-term leases for creative enterprises (Renew Australia n.d.). In reality, initiatives such as these are but short-term salves to the problems created by the vicissitudes of capitalism.

A favoured buzzword of property developers is ‘industrial heritage’, a term frequently bandied around as though it is unproblematic. In the narrative they present to the public, they are doing the noble work of taking disused and neglected former factories and industrial spaces and restoring them back to life. While the factories were places of social and economic significance in the local community during the years of their operation, the spaces they are replaced with will have questionable utility to large sections of the population, beyond a select few investors and entrepreneurs. Furthermore, ‘industrial heritage’ as it is used by developers is a sanitised concept that glosses over the realities of what it meant to labour in these spaces, realities characterised by ambivalence and struggle. This is a particular risk that arises when the supposed ‘golden age’ of industrial capitalism is reconstructed through the lens of nostalgia. As was seen in media reporting on the wind-down of car manufacturing in Australia, there is a tendency to romanticise industrial labour that was, in a large number of cases, physically gruelling and relatively unskilled. The recollections of former Ford employees are bittersweet as they reflect on many years spent in work that punished their bodies even as it provided them with occupational and financial stability. ‘The job ruined my body’, a former employee says, ‘It was such hard work. But I don’t regret it. Look at my son, he is an accountant. I didn’t have an education, and now my son is an accountant’.

In a similar fashion, the discussion around the problems facing Geelong’s CBD is haunted by the unacknowledged politics of class. While it is the visions of property developers and business groups that are realised and celebrated, the underlying issues will continue to plague the mall, and the city centre more generally, into the foreseeable future. If Geelong’s 19th century surveyors could look on the Little Malop Street mall as it stands today, they would likely be dismayed. It is a poor excuse for the ‘town square’ that they imagined the space would become. In the 21st century it is one of the most stigmatised and policed pieces of real estate in the entire Geelong region, with ‘safety cameras’ doing little to promote a feeling of safety for those who rely on the mall as a public space. Should we ‘fix’ the mall, when ‘fix’ means aesthetic adjustments that cater to the top end of town, to the tourists, investors, developers and other people who pass through this space only fleetingly, do not depend on it in any meaningful, long-term way? Who have little incentive to protect and develop the mall in ways that promote its function as a civic, rather than a commercial, space?

As Geelong pursues its ‘clever and creative’ vision, what would it mean to make the city centre inclusive and accessible for people from all walks of life? What would that look like? These questions and issues are more pressing than ever, as inclusive and safe public spaces are diminished, and many groups of people, young and old, are pushed further and further to the margins. In May 2023, the Geelong Regional Library Corporation announced that, due to financial constraints, it would likely be forced to close three branches across its network of Geelong libraries, a decision that left many people in the Geelong community aghast. The GRLC later back-tracked, stating the libraries would remain open but that hours of operation would be reduced across the network. Nonetheless, the proposal likely struck many as insensitive to the needs of those who depend on the library as a community resource, and inconsistent with Geelong’s ‘clever and creative’ ambitions.

To close, let us return to the comments of the young people that we presented at the beginning of Part One of this blog series. Emilie offered some simple suggestions for how the spaces of the city could be made more safe, inclusive and accessible for young people. In the context of the preceding discussion, her suggestions offer us much food for thought. As she says:

I think Geelong could benefit from more community centres, a community garden or free classes. Just a safe place to relax. Like, at Headspace there’s a room where if you just want to sit down and charge your phone, you can. I don’t know what that’s kind of like around the rest of Geelong, but I think that could be really good. Yeah.

We acknowledge the Wadawurrung (or Wathaurung) people of the Kulin nation who are the traditional custodians of the unceded Country where this research has taken place. We respectfully recognise past, present and future Wadawurrung/Wathaurung Elders of the Kulin nation.

References

City of Greater Geelong. 2022. ‘Greater Geelong: A Clever and Creative Future.’ Accessed 31 August 2023. https://www.geelongaustralia.com.au/clevercreative/article/item/8d4d8cdffe806c4.aspx

Correia, JA & Denham, T. 2016, Winning from second: what Geelong can learn from international second cities, Committee for Geelong, Geelong. Available at: http://apo.org.au/node/70809

Florida, RL. 2014, The Rise of the Creative Class, Revisited, Basic Books, New York.

Renew Australia. n.d. ‘Projects’. Accessed 20 September 2023. https://www.renewaustralia.org/projects