The Holocene and who we are

The Holocene represents the most recent interglacial interval of the Quaternary Period. The preceding and substantially longer sequence of alternating glacial and interglacial ages is the Pleistocene Epoch. Because there is nothing to suggest that the Pleistocene has actually ended, certain authorities prefer to extend the Pleistocene up to the present time; this approach tends to ignore humans and their impact, however. In addition, some geologists have argued that the time characterized by the rise of humanity should be separated from the time characterized by humanity’s domination over the planet’s ecological systems and biogeochemical cycles, and thus they have proposed that the later part of the Holocene should be classified as a new geologic epoch called the Anthropocene. (Rhodes W. Fairbridge and Larry D. Agenbroad (2023) Holocene Epoch: geochronology, Encyclopaedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/science/Holocene-Epoch )

In much of our work in the YPSFL we continue to situate many of the issues that concern us about young people’s pasts, presents and futures – for example, the pandemic and its consequences, the climate crisis, the crises of global capitalism, the mass extinction of bio-diversity – in wider debates and discussions about the impacts that different groups of humans have had, and continue to have, on the earth systems (atmospheric, oceanic, terran) that sustain the complexity and diversity of life on the planet.

It is important in the contexts of crisis and uncertainty – what the UN Secretary General has called a ‘code red for humanity’ (Guterres 2021), the European Policy Centre (2021) has identified as a state of ‘permacrisis’, and the World Economic Forum (2023) calls a ‘polycrisis’ – to continue to revisit these concerns as our knowledge about them is updated.

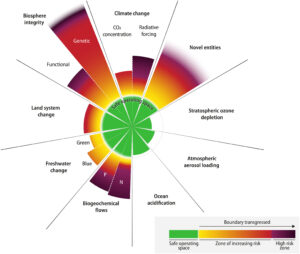

This blog emerges at a time when a group of leading scientists have just published their analysis that shows that the planetary boundaries of many of the nine vital, interconnected elements of the systems that are ‘critical for maintaining the stability and resilience of Earth system as a whole’ have been transgressed:

All are presently heavily perturbed by human activities. The framework aims to delineate and quantify levels of anthropogenic perturbation that, if respected, would allow Earth to remain in a “Holocene-like” interglacial state. In such a state, global environmental functions and life-support systems remain similar to those experienced over the past ~10,000 years rather than changing into a state without analog in human history.

Their article, titled Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries, presents an extensive analysis of hundreds of studies and articles that highlight the impacts of human activities on nine earth systems ‘boundaries’, including:

Biosphere integrity – ‘…The planetary functioning of the biosphere ultimately rests on its genetic diversity, inherited from natural selection not only during its dynamic history of coevolution with the geosphere but also on its functional role in regulating the state of Earth system…’

Climate change – ‘…The most important drivers of anthropogenic impacts on Earth’s energy budget are the emission of greenhouse gases and aerosols, and surface albedo changes…’

Novel entities – ‘…The definition of this boundary is now restricted to truly novel anthropogenic introductions to Earth system. These include synthetic chemicals and substances (e.g., microplastics, endocrine disruptors, and organic pollutants); anthropogenically mobilized radioactive materials, including nuclear waste and nuclear weapons; and human modification of evolution, genetically modified organisms and other direct human interventions in evolutionary processes…’

Stratospheric ozone depletion – ‘…is a special case related to the anthropogenic release of novel entities where gaseous halocarbon compounds from industry and other human activities released into the atmosphere lead to long-lasting depletion of Earth’s ozone layer…’

Freshwater change – ‘…To comprehensively reflect anthropogenic modifications of Earth system functions of freshwater, this boundary is revised to consider changes across the entire water cycle over land…’

Atmospheric aerosol loading – ‘…Aerosols have multiple physical, biogeochemical, and biological effects in Earth system, motivating their inclusion as a planetary boundary…’

Ocean acidification – ‘…anthropogenic ocean acidification currently lies at the margin of the safe operating space, and the trend is worsening as anthropogenic CO2 emission continues to rise…’

Land system change – ‘…This boundary focuses on the three major forest biomes that globally play the largest role in driving biogeophysical processes, i.e. tropical, temperate, and boreal…’

Biogeochemical flows – ‘…reflect anthropogenic perturbation of global element cycles. Currently, the framework considers nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) as these two elements constitute fundamental building blocks of life, and their global cycles have been markedly altered through agriculture and industry…’

The researchers represent the transgressions of these planetary boundaries in the figure below.

As they suggest, their work confirms:

that humanity is today placing unprecedented pressure on Earth system. Perhaps most worrying in terms of maintaining Earth system in a Holocene-like interglacial state is that all the biosphere-related planetary boundary processes providing the resilience (capacity to dampen disturbance) of Earth system are at or close to a high-risk level of transgression.

In a way that reflects scientific caution more than the promise of a ‘radical politics of hope’ (Braidotti 2013) the scientists suggest that their stocktake of the transgression of these limits of earth systems:

may serve as a renewed wake-up call to humankind that Earth is in danger of leaving its Holocene-like state. It may also contribute to guiding the substantial human opportunities for sustainable development on our planet. Scientific insight into planetary boundaries does not limit, but stimulates, humankind to innovation toward a future in which Earth system stability is fundamentally preserved and safeguarded.

The Anthropocene

The Anthropocene—the moment in geological time when humanity became a world-altering force—is a major step closer to formal recognition. A group of stratigraphers announced today it will nominate muds from Crawford Lake, a 24-meter-deep pond in Ontario in Canada, to serve as the “golden spike” marking the beginning of a distinct Anthropocene epoch. Chemicals and minerals in the sediments clearly capture the global “great acceleration” in fossil fuel burning, fertilizer use, and atomic bomb fallout that began in the 1950s. (Pond mud proposed as Anthropocene’s ‘golden spike,’ defining human-altered geological age)

As we have discussed elsewhere (see our other www site here) the Anthropocene – quite literally the ‘human period’ – is, in the first instance, a discourse of earth systems sciences (such as geology) which continues to be much debated (Crutzen 2002). At the same time, we must acknowledge that:

These times called the Anthropocene are times of multi-species, including human, urgency; of great mass death and extinction; of onrushing disasters whose unpredictable specificities are foolishly taken as unknowability itself; of refusing to know and to cultivate the capacity of response-ability; of refusing to be present to an onrushing catastrophe in time; of unprecedented looking away. (Haraway 2016, 39)

If ‘humans’ – in all their historical, cultural, social, economic and political diversity – are differently implicated in the emergence and consequences of the Anthropocene, then the social sciences and humanities must critically engage with, and contribute to, debates about these planetary wide changes and their different consequences in different places, for different populations.

We must take up the challenges of thinking about what the collapse of the Holocene will mean for the legacies we are bequeathing future generations.

Dithering at the Collapse of the Holocene

Over the past decades a new genre of fiction – Climate Fiction or Cli Fi – has emerged at the intersection of sci-fi and ‘speculative fiction’ (SF, Haraway 2016). In a number of spaces, I have sketched how Cli-fi entangles, in ways that are only available to these genres, with many of the themes that interest me in this blog, with the challenges of what young people’s futures might look like and why (see, for example, a blog post here).

Kim Stanley Robinson is an important and influential figure in this space, and his novel 2312, provides a name for our present. Gabriel Metcalf writes in a 2014 article from The Urbanist that:

There is also a name for the period of historical time we have entered, which I suggest we take from Kim Stanley Robinson, one of the great writers of our time: the Dithering. As seen from Robinson’s science fiction–imagined future, this is the period of human history, following modernism and postmodernism, in which humanity failed to act rapidly or decisively enough to avert catastrophic climate change. (Metcalf 2014)

This name comes from an imagined sociologist and historian whose periodisations of our futures – her pasts – resonates in our present. For Robinson’s, fictional, Charlotte Shortback, writing at the end of the 23rd century, The Dithering, was the time between 2005 and 2060: ‘From the end of the postmodern’, a date ‘derived from the UN announcement of climate change’, ‘to the fall into crisis. These were the wasted years’. The Crisis, from 2060 to 2130, saw the:

[d]isappearance of Artic summer ice, irreversible permafrost melt and methane release, and unavoidable commitment to major sea rise. In these years all the bad trends converged in “perfect storm” fashion, leading to a rise in average global temperatures of 5 K, and sea level rise of five meters – and, as a result, in the 2020s, food shortages, mass riots, catastrophic death on all continents, and an immense spike in the extinction rate of other species. (Robinson 2013, 245)

In this sense, we dither when we know we face a problem, when we know we should do something about that problem – but we don’t!

As Bruno Latour (2017, 9) has argued in Facing Gaia:

But here we are: what could have been just a passing crisis has turned into a profound alteration of our relation to the world. It seems as though we have become the people who could have acted thirty or forty years ago – and who did nothing, or far too little.

This sense of Dithering has been/is keenly felt by many young people around the world as they can imagine their futures being consumed, used up, before they arrive.

How Dare You! Young People and the Collapse of the Holocene

In another blog we introduced Greta Thunburg, the young Swedish woman who, in 2018 as a 16 year old, started a very personal form of activism by going on strike from her high school every Friday, and picketing the Swedish parliament to take more action on climate change.

To stop dithering!

Since the start of 2019 Greta has addressed various significant international forums, including the World Economic Forum at Davos in January 2019 and 2020. Videos of her various speeches have attracted millions of views on YouTube.

This is some of what Greta had to say at Davos in 2019:

Adults keep saying: ‘We owe it to the young people to give them hope’.

But I don’t want your hope.

I don’t want you to be hopeful.

I want you to panic.

I want you to feel the fear I feel every day.

And then I want you to act.

I want you to act as you would in a crisis.

I want you to act as if our house is on fire.

Because it is. (Thunberg 2019)

Yet, this latest identification of the ways in which the activities, largely, of humans in the high-income economies continue to push planetary systems beyond the limits that can sustain the rich, complex diversity of the relatively stable Holocene biosphere has gone largely unacknowledged in the media spaces that could communicate these transgressions of earth system boundaries more widely.

As the Holocene collapses, and the Anthropocene appears increasingly to be baked into the next thousands of years with catastrophic consequences for earth systems and planetary life, we continue with business-as-usual.

A business-as-usual in which many politicians and businesses promise to reach net-zero by 2050 in ways that have been dismissed as ‘green-washing’.

A business-as-usual in which the chief concerns of mainstream youth policies in education, employment, and health remain overwhelmingly focussed on the ‘skills’ young people will apparently need for the jobs of the future.

A business-as-usual that seems little affected by the protests and anger of the millions of young people energised by the figure of Greta Thunberg and the School Strike for Climate movement.

A business-as-usual in which we are all complicit if the lifestyle we have ordered is, apparently, not to be compromised. Even if it means we bequeath young people and future generations a mess that can’t be undone, can’t be cleaned up.

As Greta Thunberg exclaimed at the 2019 UN climate action summit in New York – ‘How dare you!’

This is all wrong.

I shouldn’t be up here.

I should be back in school on the other side of the ocean.

Yet you all come to us young people for hope?

How dare you!

You have stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words.

And yet I’m one of the lucky ones.

People are suffering.

People are dying.

Entire ecosystems are collapsing.

We are in the beginning of a mass extinction.

And all you can talk about is money and fairytales of eternal economic growth.

How dare you!

References

Braidotti (2013) The posthuman. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Crutzen, P. 2002. Geology of mankind. Nature. 415(23). https://doi.org/10.1038/415023a

European Policy Centre (2021) Europe in the Age of Permacrisis. European Policy Centre.

Guterres, A. (2021) Secretary-General Calls Latest IPCC Climate Report ‘Code Red for Humanity’ https://press.un.org/en/2021/sgsm20847.doc.htm.

Haraway, D. (2016) Staying With the Trouble: Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene, in J. Moore (ed) Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History and the Crisis of Capitalism, PM Press, Oakland, CA., 34-76.

Latour, B. (2017) Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime. Polity Press. Cambridge.

Metcalf, G. (2014) The Great Dithering, The Urbanist, Issue 532, https://www.spur.org/publications/urbanist-article/2014-04-10/great-dithering

Robinson, K. S. (2013) 2312. London: Orbit Books.

World Economic Forum (2023) We’re on the brink of a ‘polycrisis’ – how worried should we be? https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/01/polycrisis-global-risks-report-cost-of-living/.