‘Balochistan is primarily rural, and very few areas you can count are urban. The distant places are more vulnerable … Within those remote places, girls are the most marginalised in access to school and early dropout from school of course. Even if they go to school there is no quality at all’.

This book draws on my extensive policy and research experience about the issues and challenges concerning girls’ education in the postcolonial context of Pakistan. Building on this policy and research experience I focus on gender, education, development and rurality in Balochistan province in Pakistan.

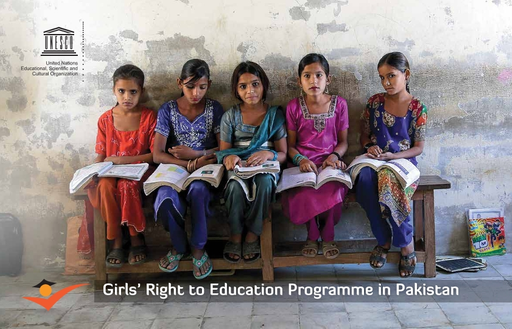

The province is characterised by its remoteness; rurality; high levels of multidimensional poverty (72%); a ‘youth bulge’ (60% under 30); low participation in education, particularly by large numbers of girls and young women (a Gender Parity Index of 0.61 [Primary], 0.62 [Secondary] and 0.55 [upper-secondary]); the lowest adult literacy rates in the country; and a marked lack of employment opportunities in rural areas.

Pakistan’s education policies identify and construct the problem of girls’ education in relation to achieving the global and national goals of gender parity and gender equality, reducing school enrolment and retention gaps in regional, urban/rural and socio-economic groups. In contrast, the low-performing education system, the increasing number of out-of-school children and particularly girls in remote rural areas show a different picture of postcolonial Pakistan.

‘The standards of education quality and teacher eligibility and recruitment have been set from somewhere else, not from here, and the people are being pushed to achieve those standards saying we are behind in literacy ratio etc. Nobody has ever done study and research here, and if someone has conducted research the lens was from outside. There was an external influence too much’.

In this context, the book charts a comprehensive account of girls’ education in postcolonial Pakistan, and argues that the problem of girls’ education in rural areas needs to be situated in the construction of knowledge, the practice of power relations, and the contested processes of truth production. Drawing on theories of Foucault’s governmentality, postcolonialism and feminism, I explore the context of Pakistan as a postcolonial Islamic nation-state, examine the British colonial legacies of governing institutions, discourses of gender and education, and development of girls’ education policy and practices. The book makes a significant contribution to the development of the analytical framework of postcolonial Islamic governmentality, and uses the framework to analyse the research data, and education policy texts and discourses.