Why, what and how: an education for now, for the future

At the end of 2019, as the world looked forward to the dawn of a new decade, we as humanity could not have imagined what the 2020s would hold for us both individually and collectively for the planet. In a 2022 article in The Conversation, Professor of Philosophy at Nottingham Trent University, Neil Turnbull, states that:

Permacrisis, which the Collins Dictionary defines as “an extended period of instability and insecurity,” was chosen as the Word of the Year for 2022, and it’s fitting that it be chosen because it perfectly captures the disorienting feeling of lurching from one unprecedented event to the next, as we wonder bleakly what new horrors may be around the corner.

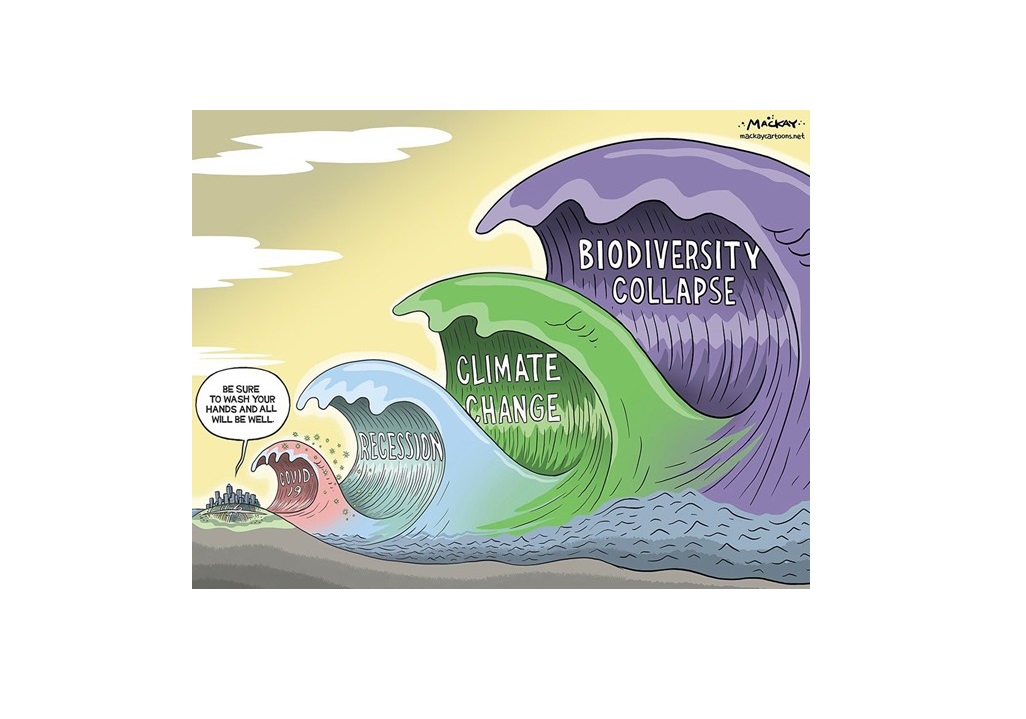

This permacrisis was a wake-up call to humanity, defined by an ongoing pandemic that changed the lives of all people, as governments worldwide grappled with the conflict between saving human lives and preventing global economic collapse. As the world emerges from the pandemic’s immediate threat, with outbreaks still occurring, and the actual cause being debated, the crisis continues to evolve. According to financial services firm S&P Global (2023) we are experiencing ongoing geopolitical risks, including global economic insecurity and inequity of wealth distribution. The Russia-Ukraine conflict has contributed to the reorganisation of global structures and relationships. With energy and climate change continuing to be politically polarising issues, and global progress notably lacking on climate action, there are far-reaching implications for our survival now and for future generations.

Turnbull (2022) goes on to explain the interconnectedness of all the crises, highlighting the difficulty we face in solving these problems:

Our crises have become so complex and deep-seated that they can transcend our capacity to understand them, and any decision to tackle them risks only making things worse. We are thus faced with a troubling conclusion: Our crises are no longer a problem. They are a stubborn fact. Permacrisis signals not only a loss of faith in progress but also a new realism in relation to what people can cope with and achieve.

Surprisingly, despite all the technology, innovation, and connectivity that we have generated, humanity was left confounded by a virus. The COVID-19 pandemic emphasised the fragility of our planet and of the humans who reside and depend on it.

In Jenny Andersson’s (2022) blog An economy of Place- Part 1 she explicitly states that:

The experience of the global COVID-19 pandemic has cast a bright light on the frailty in our global economies, has highlighted our inability to adjust to complexity, uncertainty, and volatility, and accelerated the conversation about what needs to change in our world. Not just to adjust to the possibility of future viral anomalies, but to the greater challenges following in its wake. Climate change. Biodiversity loss. Soil degradation. Ocean acidification. Economic and social collapse.

This permacrisis is a catalyst for change and the disruption that is required to look at alternative pathways and ways of thinking.

Zhao (2020, pp. 30-31) suggests that COVID-19 can become an opportunity for reimagining education: ‘Schools are institutions for education, but they were built at a time when human understanding of learning and learners, knowledge and skills, as well as teaching and teachers was different from today’. The pauses to education caused by the pandemic ‘give governments and educational leaders the very rare opportunity to rethink education’, including the possibility of students designing their own learning. Zhao argues that the COVID-19 pandemic should prompt schools to question whether learning only takes place in the classroom, and to ask, can we start learning by asking students to use inquiry methods to identify problems and conceptualise solutions?

In the context of what Turnbull and others have called a permacrisis, the Young People’s Sustainable Futures Lab (YPSFL) has sketched the outline of a project broadly titled: Regenerating Geelong: Young people and the futures we make with, for and alongside them. The project, as it is currently framed, seeks:

- To work with, for and alongside young people to re-imagine the education, training and employment systems, practices and knowledges that are fit-for-the-purpose of regenerating capitalism in these regions;

- To develop collaborative partnerships to co-design the new, disruptive, transformative, and ethical economic and livelihood models that can emerge from, and contribute to, the regeneration of capitalism in particular places in Greater Geelong and the Great South Coast.

In this project, the YPSFL draws on various concepts to think about the possibilities offered by a regenerative mindset. These concepts include:

- Regenerative capitalism – which ‘refers to business practices that restore and build rather than exploit and destroy’;

- Regenerative agriculture – which seeks ‘to build natural and social capital, and transform food and fibre systems’;

- Rewilding – which seeks to move beyond just preventing further extinction of flora and fauna, and restore what we’ve lost.

Through this series of four blogs, I will seek to explore, through an extensive review of the relevant literature, the question of ‘Can a pedagogy of regenerative education and related learning theories, support young people’s ongoing wellbeing during the permacrisis?’ This pedagogy is framed on a compassionate system agenda, drawing on a range of learning theories including inquiry-based learning (Definition 1), systems thinking theory (Definition 2) and social emotional learning (Definition 3). I will also show how these learning theories can support wellbeing through student empowerment, connection to place and constructing and repairing connectedness in a time of isolation.

This review of relevant literature will form a thematic map to distil the key themes relating to regenerative systems thinking. In undertaking this research, I aim to contribute to the further development of the YPSFL project, and to ongoing educational debates about our current system and its suitability to equip students to become change agents of their learning and how alternative pedagogies can be adopted throughout all sectors of education. This series of blogs does not intend to offer a panacea or solution to the crises we face. Rather, it contributes to the ongoing conversation around our current education framework, its ability to meet future requirements of young people and how looking through a regenerative lens can change the way we currently approach the world problems we face today, with hope for the future.

Education is fundamental to positive outcomes regarding sustainability and regeneration of our planet. Giangrande et al. (2019) outline the overarching concept of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), a framework generated from UNESCO Sustainable Development Goals, especially goal 4.7 (UNESCO, 2015). According to UNESCO (2017, cited in Giangrande et al. 2019, p.2), ESD:

Empowers learners to take informed decisions and responsible actions for environmental integrity, economic viability and a just society, for present and future generations, while respecting cultural diversity. It is about lifelong learning, and is an integral part of quality education. ESD is holistic and transformational education which addresses learning content and outcomes, pedagogy, and the learning environment. It achieves its purpose by transforming society.

In his article A Regenerative Education for our times (2020), educator and organisational consultant Giovanni Ciarlo suggests that ‘the current education paradigm holds the idea that the sole purpose of education is to educate individuals within their particular society, to prepare and train them for work in an economy that integrates people into the national cultural reality and passes on the value and morals of that society’. The emerging theory of regenerative education, on the other hand, promotes a vision of ‘an education that serves people and the planet as we move into a new environmental reality, with its accompanying social shifts, economic transformation and understanding of who we are as a species and an individual’.

Buckton et al. (2023, p.826) suggest that when regenerative perspectives and practices are adopted in education:

Teachers create conditions for the emergence of creativity and mutualism, including transdisciplinarity (Definition 4) and finding inspiration from nature, drawing on ideas from regenerative design. Students are not just taught about environmental crises but are also given the wisdom and skills to encourage regeneration and flourishing of life. Sustainability education is decolonised and recentred on Indigenous histories, concepts and wisdom.

Regenerative education is a holistic framework to empower students and foster lifelong learning, that allows them to grasp the interconnections between systems, whether they are ecological, social, or economic. It promotes a shared responsibility for our future, drawing on and integrating knowledge from multiple disciplines, while emphasising social justice. It aims to foster innovative and collaborative thinking to solve complex problems while creating positive environmental and social outcomes contextualised to the learner’s community.

In the Gonski Report (Gonski et al. 2018) the current education framework was described as an industrial model of school education that is focused on ensuring millions of students attain specific learning outcomes but that does not incentivise schools to innovate and continuously improve. So much has evolved worldwide since 2018 and at such a fast rate that even if change had been implemented based on the Gonski Report it could not have prepared our young people for a global pandemic and the ongoing challenges this presents. Regenerative education should be investigated not as an alternative or extra content to deliver but something that can be incorporated within the curriculum of the current framework of education policy. This framework is one that can make young people feel empowered to act, create a connected community, support their ongoing well-being, and bring a sense of equity.

Finally, at the end of the final blog in the series I include a Glossary of some of the key concepts I use, and full reference list of the sources I have cited.